Donny reviews a graphic novel with some frikken’ amazing art.

Cages

By Dave McKean

#’s 1-10 published 1990-96

Collected book published in 1998

Coming in at 500 pages, this is certainly one of the longest graphic novels in my library. Dropped from a window, you could easily kill a man with this weighty tome. However, it’s a comparatively fast read. It relies more on pictures than words – but it makes you want to linger on those pictures… because it’s probably the best drawn comic book that has yet been made!

Dave McKean had illustrated a string of remarkable and beautiful graphic novels in the late-80’s including Violent Cases (with Neil Gaiman, 1987) and Arkham Asylam (with Grant Morrison, 1989). Those beautiful works of art relied on a lot of lush, Barron Storey-influenced, heavily mediated illustrations that employed collage, painting, sculpture, and Photoshop manipulations. However, McKean then rejected that as being the wrong choice for comics saying that the art “just calls attention to itself too much,” (McKean in Artists on Comic Art by Salisbury, 2000). “I’m not sure if it’s really appropriate for the comics work I’ve done. For the covers, maybe, because that’s an illustration, but not necessarily for the actual storytelling,” (McKean in Comic Book Rebels by Wiater & Bissette, 1993). He felt that his painted, heavily mediated books became labored, and that comics required a simpler, immediate style to tell the story directly and easily. Thus, for Cages, he paired it down to quick, direct, sketchy line drawings that are breathtaking.

Cages opens with four different, prose creation myths. Much of the book develops the analogy between divine and artistic creation, and imagines God as an artist trying to fill blank pages with something new. Actually, a good way to read Cages is as a clash between this artistic view of God (of creativity, metaphor, freedom, and flight) and an Old Testament, fire-and-brimstone God (of cages built of fear, guilt, and social controls).

If I have one critique about this book it comes at the very beginning. Rather than putting all the prose stuff up front, it would have been much better to space it out throughout the comic. As it is, it slows things down too much right at the beginning when you have to read through a dozen pages of prose before you get to the sequential art. My recommendation to you: read the first myth, then read the first three chapters, come back and read the second myth, read the next three chapters, and so on.

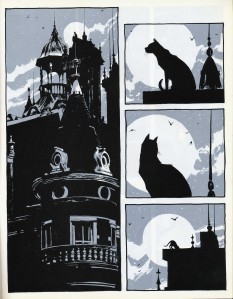

After the prose prolog, the comic finally opens with a wonderful sequence where a wandering cat introduces us to the residents of an apartment building. It remains one of my favorite opening sequences in all of comics. The windows of this building allow the cat to see into the past or future. The only explanation we get for how that works comes in the form of a parable about a pretentious king building a tower as a home for artists, musicians, poets, zoo-keepers… well, the tower is obviously an analogue for the apartment building. (But the tower is just as obviously the graphic novel itself – and it’s also Jonathon Rush’s fictional novel, Cages, within the story, which is illustrated with a tower on the cover.) I’m getting too far ahead, but I just wanted to make the point that the only explanations we get for anything in Cages come in the form of parables and allegories. Readers who demand tidy endings and Ms. Marple explanations will be left very confused and disappointed.

On the street, the cat meets Leo who is moving into the building. He’s an artist seeking to escape from “real life” for a while (and will end up discovering inspiration, religion, and love along the way). Leo runs into a nut named Jeffrey (the first of a host of crazies we will meet) who asks him the first philosophical question of the book: “Don’t you see how tiny we are? How we are all just prawns [sic] in God’s great chess game?” (McKean has a fondness for malapropos.) So, McKean is taking on no less than our place in the universe vis-à-vis God. What does life all mean? What does it all add up to? And he’s already given us some “answers” in the form of the various creation myths. We create meaning in the stories and myths that we tell and the art we create. But I got ahead of myself again, didn’t I?

Next, Leo bumps into a bum who comically takes Leo’s, “What do you want?” as an existential question. “A bit of companionship. Maybe something to be working at. A sense of identity, spiritual identity.” Of course this is exactly what Leo is really seeking (and will find by the end of the book). A love of malapropos and comic (and profound) equivocations runs through here, and there’s a strong touch of Shakespeare’s humor at play, I sense. There are also a few nice soliloquies spoken directly to the reader and fourth-wall breaks. One of my favorite of such asides comes on p.82 of the collected edition where for one panel Leo just looks directly at us with an expression of, “Can you believe this shit?”

To make a long story short (too late!): Cages is (sort of) about a painter who moves in to this (magic) building full of eccentrics where he meets two other creators: Angel, a jazz musician who might be an actual angel (or at least a sorcerer) and Jonathon Rush, a Salman Rushdie-inspired novelist who is under a kind of Kafkaesque house-arrest… from there, and through some other characters (like the shut-in Ms. Featherskill who spends a long chapter in monologue with her fowl-talking parrot) it explores questions about art, music, loneliness, creativity, myth, religious zealot-ism, God, and – of course – cages. The multitalented Dave McKean is, himself, a painter, a writer, and a jazz musician (as well as a filmmaker), so he’s basically split himself in three characters (Leo, Angel, and Rush) for this hypnotically meditative novel.

It is a work of magic realism of the kind made famous in comics by Neil Gaiman, McKean’s friend and frequent collaborator. The time-shifting windows in chapter one were subtle… but then chapter three opens by having the scaffolding around the building (scaffolding is a recurring image, along with towers) transform into a pair of giant skeletal birds and fly away. Why? Mostly just because it’s beautiful and mysterious… but later in the chapter Leo watches another pair of birds take flight (birds – especially pigeons – skeletal or otherwise, sometimes talking, are another recurring image). Leo tells Rush that he is artistically blocked due to fear of freedom. Rush gives a bitter laugh and explains: “Everybody’s a bird, locked up in a pretty cage. Sometimes you fly to a slightly bigger one, but you never quite have the courage to abandon captivity altogether.” (Of course, the climax of the story involves Rush leaving his cage.) It’s then that Leo sees the pair of birds take flight out the window – which may be the pair that used to be scaffolding around the building. The scaffolding formed a kind of cage around the structure, and their departure signals that Leo’s arrival is going to set some of the imprisoned tenants free.

Cages has a quality similar to Richard Linklater’s films: quirky, pretentious, philosophical artist-types in dialogue. This is a book that feels more like a piece of music than a novel as conventional storytelling frequently takes a backseat to the current riff. Some of the best sequences are silent: notably the scene where Leo and Karen fall in love while talking the night away in the jazz club… and the silent pages where they make love is possibly the best drawn sex scene in comics. It’s visual music. You must read this book while listening to jazz music, though. No, really. I insist. You must.

The opening words from chapter four give us another clue how to read Cages: “Slowly, the individual lines begin to describe something.” The individual stories are told in a back-up and loop around, non-linear manner, and it requires some close reading to keep track of when each episode is taking place (if it’s even possible to work out exactly). However, as the book nears its end, the individual plot threads to start to some together… but only just start to.

In the jazz club, Angel takes the stage he tells us another creation story, but this one is mostly a warning to artists about the dangers of either over- or under-refining a work – and he could be talking about Cages itself. McKean has explained that he prefers to leave an artwork “incomplete,” so that the artist provides only 50% of the creation. The audience must provide the other 50%, and the real work of art exists in each of the viewer’s heads. Although the final chapter gives us some hints about how this strange world works, there are ample loose ends… and I find one of the most intriguing questions to be: Who is the cat on the last page of the book (who may or may not be the same cat from the first page), and what does his final act mean?

McKean’s drawings are so, damn good! The line art can, by turns, be weightless or moody, eloquent or mad. McKean has taken the vanguard artistic creativity and visual range of Barron Storey, but here, more so than in his previous works, he’s integrated it with the storytelling skills and cartooning chops of Will Eisner… and thus he’s created what I think is the best drawn comic book ever. Like Alan Moore, he uses some great formal devices in each chapter. “Descent” is constructed on a downward movement. “Ascent” reverses the movement. “Schism” employs a kind of mirroring across the horizontal axis. “Blank pages” uses blank white surfaces as match-cuts. And he also uses what must be the coolest POV sequence in comics: in chapter eight when we get a sequence seen through the eyes of the cat.

His drawings are so good and his muted plot so strange that I think McKean’s excellent dialogue often gets overlooked. He is a very good dialogue writer. He understands the value of a surprising choice of words: saying, “and out comes this absurd set of paws with a dog attached called ‘Lemon,’” instead of just saying, “out came a dog named Lemon.” He also has a fantastic ear for naturalism because in writing the book he acted out all the parts into a tape recorder in order to best capture natural speech patterns and give each character a distinctive voice.

The book risks being pretentious, but it saves itself by being self-aware. Its characters often take the Mickey out of one-another’s deep thoughts. McKean even ironically writes his own book review. When Rush critiques a book he’s finished reading, he could just as well be talking about the book he is in: “He wears his influences a little too loudly, he has a tendency towards fashionable pessimism, but on the whole quite a remarkable book.” When Leo complements Rush on his first book (“It was an impressive debut,”) Rush replies, “It was pretentious drivel. If there was ever anything valid there, it was trivialized by superficial, stylistic veneer.” This seems to be McKean talking about himself. Some have interpreted this as another winky shot at Cages, but I think, rather, that McKean is, here, criticizing his early works. After all, Leo and Rush are, in the story, talking about Rush’s debut novel – not his most recent book, Cages – and I’ve heard McKean use almost those exact words dismissing Arkham Asylum as a pointless Batman potboiler dressed-up with a lot of pretentious words and pictures.

I called the story “muted,” but that isn’t a criticism. “Comics is an intimate, one-to-one experience. It’s even more intimate than a novel… It’s very much like a postcard or a letter… So it seems to me to lend itself to very introverted stories… It comes down to this idea of comics working best when they’re like something handwritten, like a postcard.” (Comic Book Rebels). This sounds very much like Art Spiegelman’s approach to Maus: wanting it to have a “diary feel,” he drew Maus all on small copier paper with pens he picked up from a stationary store.

Cages may be the most solid proof to-date that comics can be a literary art form. I would argue that Cages can comfortably go on the same shelf as Ulysses, The Metamorphosis, and 100 Years of Solitude. Beyond that, I can’t overstate my pleasure in re-reading this book. I first acquired it in the 1998 collected edition, and this is my third time reading to through since then, and my appreciation for this work has grown each time. I expect it will remain a book I will continue to enjoy re-reading every eight or ten years. If you’ve never read it, you’re missing out on something magic.

Pingback: 1993: Cages | The Entire Kitchen Sink