Donny reviews the Emerald Duo.

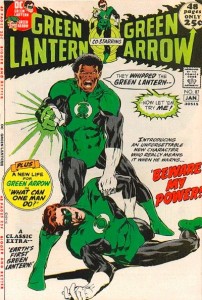

Green Lantern/Green Arrow

1970-1973

Dennis O’Neil (story)

Neal Adams (art)

Green Lantern/Green Arrow #76, February, 1970, announced a new direction by opening with the surprising words: “For years he had been a proud man! … His name, of course, is Green Lantern, and often he has vowed that ‘No evil shall escape my sight.’ He has been fooling himself.” Flying over the city, Green Lantern sees a “punk” shoving an upper-class white man wearing a suit. When he jumps in to ‘teach the punk a lesson,’ Green Lantern finds the whole (poor and mostly black) neighborhood throwing trash at him. (Remember, black people had rarely ever been depicted in DC comics at all before this.) He calls them “animals” (racist much, GL?) and “anarchists,” and spits at them, “You want a riot!?” (Is he in Ferguson? Baltimore?) Green Arrow appears and explains that the white guy in the suit is a slum lord who is evicting all these people. Then comes one of the top-10 most famous scenes in the history of comics: An old black man comes up to Green Lantern and says: “I been readin’ about you… how you work for the blue skins… and how on a planet somewhere you helped out the orange skins… and you done considerable for the purple skins! Only there’s skins you never bothered with… the black skins! I want to know… how come!? Answer me that, Mr. Green Lantern!”

Green Lantern looks shamefully at his feet and mumbles, “I… can’t…”

Whoa! Nobody had ever seen this before in DC comics!

Batman (who was also getting a darker, grimmer Denny-O’Neal-Adams makeover at this same time) is the ultimate detective, solving crimes. Superman is the ultimate fireman, rescuing us from disasters. Green Lantern is the ultimate cop, enforcing the law… and yet he was guilty of unconscious racism and class-ism. Was DC’s emerald titan really just Darren Wilson with a cosmic power ring? The Green Lantern turned out, in the words of Grant Morison, to be the “bewildered representative of every dumb-ass cop who ever pounded the beat; the unthinking stooge of geriatric authorities from a galaxy far, far away” (Supergods, 2011).

Irish Catholic Denny O’Neil – young, intense and opinionated – came out of the newspapers and said that he still “considered myself as much of a journalist as a fiction writer,” (Jones and Jacobs, The Comic book Heroes, 1997). He came from the opinionated “new journalism” school of Tom Wolfe, Norman Mailer, and Hunter S. Thompson. “Could the comic book equivalent of the new journalism be possible?” O’Neil asked. “What would happen if we put a superhero in a real-life setting dealing with a real-life problem?”

Was this really a groundbreaking idea, though? To be fair, over at Marvel, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby had been using black characters since ’63 and Roy Thomas was writing about racial issues since ’68, so was this really only lily-white DC catching up? Shortly after Green Lantern’s humiliation at the hands of an old black man, Marvel had Captain America become a motorcycle cop in his secret identity and partner up with Falcon, a black, Harlem social worker turned crime fighter. O’Neil responded by introducing John Stewart, the first black Green Lantern. Stan Lee did a Spider-man story over at Marvel about the dangers of drug addiction, so, at DC, O’Neil made Speedy a heroin addict. Again and again, Marvel tended to lead the way and DC followed.

I guess what really made GL/GA such a milestone is just how explicitly political it was. Green Lantern was a member of the Green Lantern Corps, a cosmic police force. “My whole life,” he says, “is based on respect for authority.” Green Arrow was once a wealthy CEO who lost everything (like Robin of Loxley losing all his lands and titles to Prince John). O’Neil saw the Green Lantern as a right-leaning, peace-keeping enforcer of the establishment. Green Arrow, the modern Robin Hood, was the voice of populist, class-warfare radicalism. The idea was to partner the characters up to let them debate one-another like Point Counter Point while fighting bad guys. Together, they defended a mine-workers’ union, fought against a Manson-inspired racist cult, protected Native Americans’ land rights against loggers, took-on an over-eager judge handing out death sentences like Halloween candy, and dealt with pollution, overpopulation, radical feminism, race riots, and the creepy side of consumer-capitalist culture.

O’Neil was a Leftist and it’s obvious where his sympathies lie. He even described Green Lantern as having “noble intentions, but still a cop, a crypto-fascist” (1997). I guess he somewhat balances the scales by making Green Arrow an insufferably self-righteous prick, the caricature of the righteous bleeding heart, the preachy hippie that drives conservatives nuts. It makes a problem for the reader, though: by turns both Green Lantern and Green Arrow can be pretty annoying. Listen to this diatribe GA hurls at GL: “You call yourself a hero! Chum… you don’t even qualify as a man! … There are children dying… honest people cowering in fear… disillusioned kids ripping up campuses… On the streets of Memphis a good black man died… and in Los Angeles, a good white man fell… Something is wrong! … Some hideous moral cancer is rotting our very souls!”

Yeah, it can be laid on a bit thick…

And problematic. The Native American story tries to be sympathetic, but re-read today it has some pretty cringe-educing moments like when Green Arrow refers to them as his “Redskin brothers.”

On the other hand, most comic book dialogue up to this time was just as unrealistic. No, the biggest problem I have with these comics is that the endings of each story are almost invariably unsatisfying – unsatisfying because they are too easy. O’Neil takes on these complex, real-world problems… but then he contrives some way to conveniently wrap it up in the last couple of pages so the good guys win. In real life, the 1% usually aren’t overt crooks or maniacs who get hauled off to prison – and don’t have to be in order to wreak havoc on society and the environment – but here, they always turn out to be crooks or maniacs so that they can be conveniently hauled off to jail. This also makes it too easy for GL to resolve his personal dilemmas each time – until the climactic story.

Before we get to that: One of the better story moments has GA get stabbed by a mugger. As he crawls around seeking help, he is ignored by several pedestrians. This was a call-back to the 1964 murder of Kitty Genovese in Queens when a reported 37 people saw her being attacked (stabbed multiple times), and no one called the police. One witness was infamously quoted in the papers: “I didn’t want to get involved.” In 2010 this tragedy would play out again with the public killing of Hugo Alfredo Tale-Yax who bled to death on a sidewalk while at least 25 people walked past him. This story in GL/GA really shines a light on the difference between the liberal and conservative worldviews. In the conservative view, the solution to street crime is more cops (and more violent – Dirty Harry type – cops) and harsher sentences. I always think of a line in Death Wish: “What this city needs is more cops than people.” But O’Neil’s story depicts the mugging from the 1960’s liberal perspective, and what’s really needed, from here, is for us all to do a better job of caring for one-another, looking out for one-another, and being good Samaritans. The real problem is indifference, greed, lack of compassion, and not wanting to get involved.

Another favorite of mine was “Peril in Plastic.” Marx said, “Religion is the opiate of the masses.” Mathew Slaughter said, “Television is the opiate of the masses.” This story is about mass brainwashing which the villain gloats “makes the rubes happy, is what! Take away ambition… curiosity… and you got perfect employees!” It’s a pretty good metaphor for modern capitalist consumer culture. Work your job, buy your crap. Work your job, buy your crap. This story has one of the better endings, too.

The justifiably famous, two-part drug story is pretty good. The self-righteous hippy, Green Arrow discovers his ward and sidekick, Speedy, is a heroin addict… and throws the kid out of the house. However, again, the ending is too easy: Speedy appears to kick his drug habit in two issues.

The introduction of John Stewart is good. No, not the host of The Daily Show; the first African American Green Lantern. To contrast him directly with Hal Jordon (calling back to issue #76), Stewart is introduced standing up to a bullying cop. He makes a great character: kind of the Samuel L. Jackson of the Green Lantern Corps. It’s a shame he was, here, underused.

The climactic story is also pretty good. It involves a tree-hugging, Jesus-look-a-like, eco-fighter named Isaac. GL’s girlfriend, Carol Ferris, owns a big, Boeing-like aircraft company. Her company is polluting the environment, but she responds, “All I can say is, we’ll solve the environmental difficulties when they arise!”

To this, GL, like an idiot, adds, “I believe it! American technologies can generally solve [anything].”

This story does suffer from putting its Jesus metaphor ridiculously in your face. O’Neil didn’t trust his readers to get it unless he has Isaac literally crucified between GL and GA and has the man in charge say, “I wash my hands of it,” while GA defends Isaac/Jesus by shouting, “He’s just trying to help us all! Don’t you see?” There’s even a freak’n dove that takes flight when Isaac dies on his cross. However, the ending is still pretty good. Green Lantern’s industrialist girlfriend rationalizes, “I suppose progress must always claim victims!” Green Lantern finally snaps and does what he’s stood against all this time: he takes the law into his own hands and just wantonly destroyers her experimental planes.

I must say, Neal Adams’ art is fantastic. He’s clearly one of the best artists of the 1970’s – making superheroes look more real than ever before, and there are some great page layouts that appear to be very influenced by Will Eisner. However, in the end, I largely agree with Jones and Jacobs (1997) that it’s “too bad GL/GA wasn’t as satisfying as it was important.” A little more from them: “The charmed suspension of disbelief that makes a purely fanciful battle of superhero and supervillain plausible can no longer be sustained when the hero starts grappling with unions and polluters. ‘Concretizing the symbol,’ the mythologist Joseph Campbell called it, and it’s the quickest way to deprive any symbol of genuine mythic power.” Today we just call it “a little too on the nose.”

All around, this book is subtle as a sledgehammer – and not just in its overt political messaging. After the heroes get attacked by a flock of birds, for instance, there is a cameo of Alfred Hitchcock walking by dressed as a mailman – which would be really cute, except that O’Neil has one of the characters say, “It reminds me of that Alfred Hitchcock movie.” That’s this book right there. It’s O’Neil constantly distrusting his readers to figure out or notice anything unless he makes it crazy obvious.

Still, it deservedly is an important work. This book is a watershed in the history of comics – a milestone for the beginning of the Bronze Age. “It was time,” writes Grant Morison (2011) “for comic-book superheroes to tap into the same self-critical, antiauthoritarian cultural energy source that would drive The Godfather, Dirty Harry, Death Wish, and Midnight Cowboy.” So long, escapist fantasy. Welcome to the desert of the real.

Pingback: Hot Streak: Nick Cardy’s Aquaman – Who's Out There?